A Brief History of Reproduction

No, no, no – not the baby making kind! The blueprint kind. I’ve been thinking about this subject because a client just showed me the original blueprints of a house his parents built in 1938. That deep velvety blue background with white lines obviously drawn with a pencil reminded me of my early days using a T-square and drafting board.

Early building illustrations were one offs, and they were not always two dimensional. The Romans would carve full size façade templates into large stone paved areas. Renaissance furniture makers invented perspectives using inlaid wood of different colors on cabinet doors.

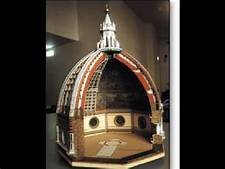

Intricate wood models of buildings, like Brunelleschi’s model of the Duomo, might occupy an entire room. Carvers would carry miniature carvings as samples. More common were ink drawings, on vellum (chalk powdered skin) in the West and paper in the East. None of these illustrations could easily be reproduced.

Reproduction and printing was first developed around 200 AD by the Chinese. They created wood block printing on cloth to create patterned fabrics. By the 7th century it had evolved to print books on paper. In the 15th century this technique had diffused into Europe. However, illustrations were still rare. For example, first century Roman architect Vitruvius’ 10 volume De Architectura Latin treatise on architecture was hand copied for centuries before being translated and printed with illustrations by Cesare Cesariano in 1521. In the same century, the Italian Renaissance architect, Palladio, set a new standard for architectural pattern books with his large format folios illustrating classical architecture, printed with intaglio copper plates.

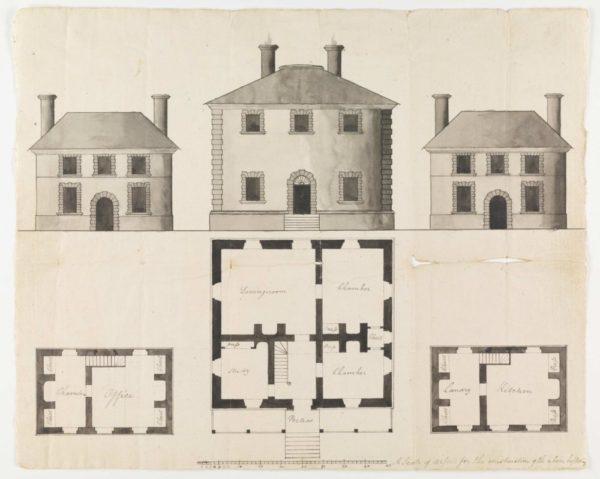

But none of these printing advances changed the basic system of hand drawing with ink to design and construct buildings. The 1769 ink on vellum drawing (above) of one of Encore’s projects, Menokin, a Virginia Northern Neck plantation house, shows the first floor and front façade of the main house and two outbuildings. As far as we know, that was the complete set of plans used to construct the Palladian style buildings.

To make copies of drawings such as these, thin, hand-made, cotton rag paper was laid over the vellum sheet, and the drawing was hand traced. The graphite pencil was invented in 1795 by one of Napoleon’s engineers, and it slowly supplanted ink for initial drawings. But it wasn’t until the mid-19th century, that mechanically made wood-fiber tracing paper and vellum became much less expensive than rag paper or animal skin.

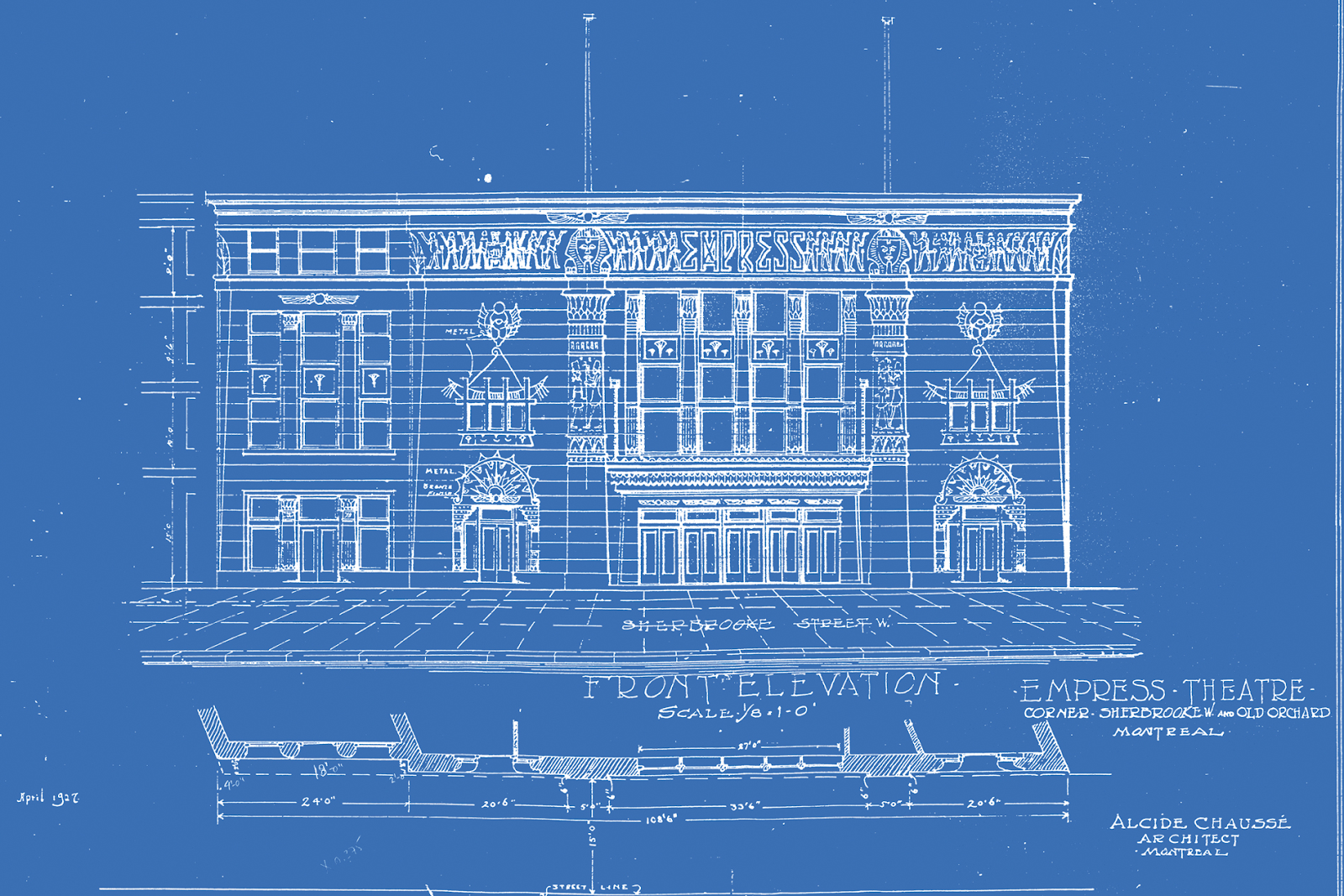

So, how did the actual “blueprint” come about? The chemistry of the blueprint process was discovered by British astronomer and photographer Sir John Hershel in 1842. A translucent drawing is laid on a chemically coated paper and exposed to ultraviolet light, then exposed to ammonia gas. The shaded areas below lines remain white while most the paper remains blue. The process can be repeated to produce many sets of drawings. Blueprinting became so universal that even today a set of building plans is often called “the blueprints.”

In the 20th century the Diazo process, which produces “whiteprints” (dark blue lines on a white background), replaced blueprinting. In turn, nearly all drawing printing is now done by digital scanning and printing, officially known as Xerography after being invented by the Xerox Company.